Chapter 1 - Elucidating models of ambidexterity and their boundaries for innovation management

In this first chapter of literature review, we propose to start discussing the seminal paper by James Gardner March published in Organization Science in 1991 entitled: “Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning” (James G March 1991). We, of course, put this article into perspective with the flourishing streams of literature which have rooted their assumptions in the problem-based and decision-making background mobilized by J.March.

The introduction of the manuscript highlighted that the streams of literature of organizational ambidexterity could be revisited by developments in innovation management, such as exploration project management. This preliminary assumption is induced by the limitations raised by several authors in the field of ambidexterity, specially on the how to achieve such model (Birkinshaw and Gupta 2013; O’Reilly and Tushman 2013; Benner and Tushman 2015). And it is also backed up by the organization studies dimension challenging project management (Sydow, Lindkvist, and Defillippi 2004; Bakker et al. 2016; Söderlund, Hobbs, and Ahola 2014; Söderlund and Müller 2014) and more specifically exploration project management, tightly linked to innovation management literature (Lenfle and Loch 2010, 2017; Davies, Manning, and Söderlund 2018).

The several challenges, in the literature briefly discussed so far, point at the tensions and fuzziness at the crossroads of innovation management and organizational studies. More precisely, the original assumptions of exploration vs. exploitation for organization learning and adaptation may be now in conflict with the engines of innovation: managing the unknown through project management. The unknown has gained ground over time up to the point where models of ambidexterity may no longer be valid. It is this interaction between ambidexterity and the unknown that will guide our literature review. We are keen on understanding what happens at the potential edges of ambidexterity’s validity domain. We propose then to start anew with the foundational paper (James G March 1991) on which literature piled up.

The notion of exploration and exploitation were typified in the well-defined situation of problem-solving and associated decisions to balance off these two constructs for organizational learning and firm competition for survival and primacy. The first section 1 elaborates on the model and its boundaries as defined by J.March. These boundaries have separated it from the unknown, whereas it has been feeding streams of literature in innovation management, organizational structure and performance.

The second section 2 discusses the latter with the emergence of the organizational ambidexterity construct and prescription of organizational designs supporting innovation. Limitations identified by major researchers in the field are reported opening the debate on the micro-foundations of ambidexterity.

Finally, the third section 3 looks at generative processes and their contributions to exploration and exploitation. It allows us to extend the behavioural roots of problem-solving and decision-making with design reasoning.

Balancing exploration vs. exploitation: an incomplete model?

In (James G March 1991), James March presents a model supporting a Schumpeterian view of a firm’s sustainability with an organizational learning perspective: exploiting old certainties or exploring new possibilities. The firm is described as a system, where choices are made within the organization to engage in exploration or exploitation.

[..] maintaining an appropriate balance between exploration and exploitation is a primary factor in system survival and prosperity. (James G March 1991, 71)

The trade-off discussion is developed with a reference point taken in rational models of choice. A decision problem is then composed of: a set of states of nature $S$ from which consequences are envisioned $X$ with associated probabilities $\mu$, a cost function $c:x\in X \rightarrow y\in\mathbb{R}^+$ and the decision-maker is requested to build up decision function $d:s\in S \rightarrow x\in X$. Several axioms are necessary to support the theory depending on the model used, and the simplest version can be found in (Wald 1945, 1949), corresponding to basis on which (Savage 1954) and (Raiffa 1968) have developed in management education (Giocoli 2013; Fourcade and Khurana 2013). But before considering the decisional dimension, it is worth noting the conception of action: problems appear to the agent, who then calculates accordingly given previous statistical learning from the past and additional information available on the spot. The calculation is seen as suboptimal given the limited/bounded rationality of the agent and the collective in an organizational context (Simon 1955). The organizational behaviour is then focalized on the agent, its beliefs and interactions with others and available information. It allows then envisioning the contribution to the performance and survival of the firm as beliefs evolve and the environment changes.

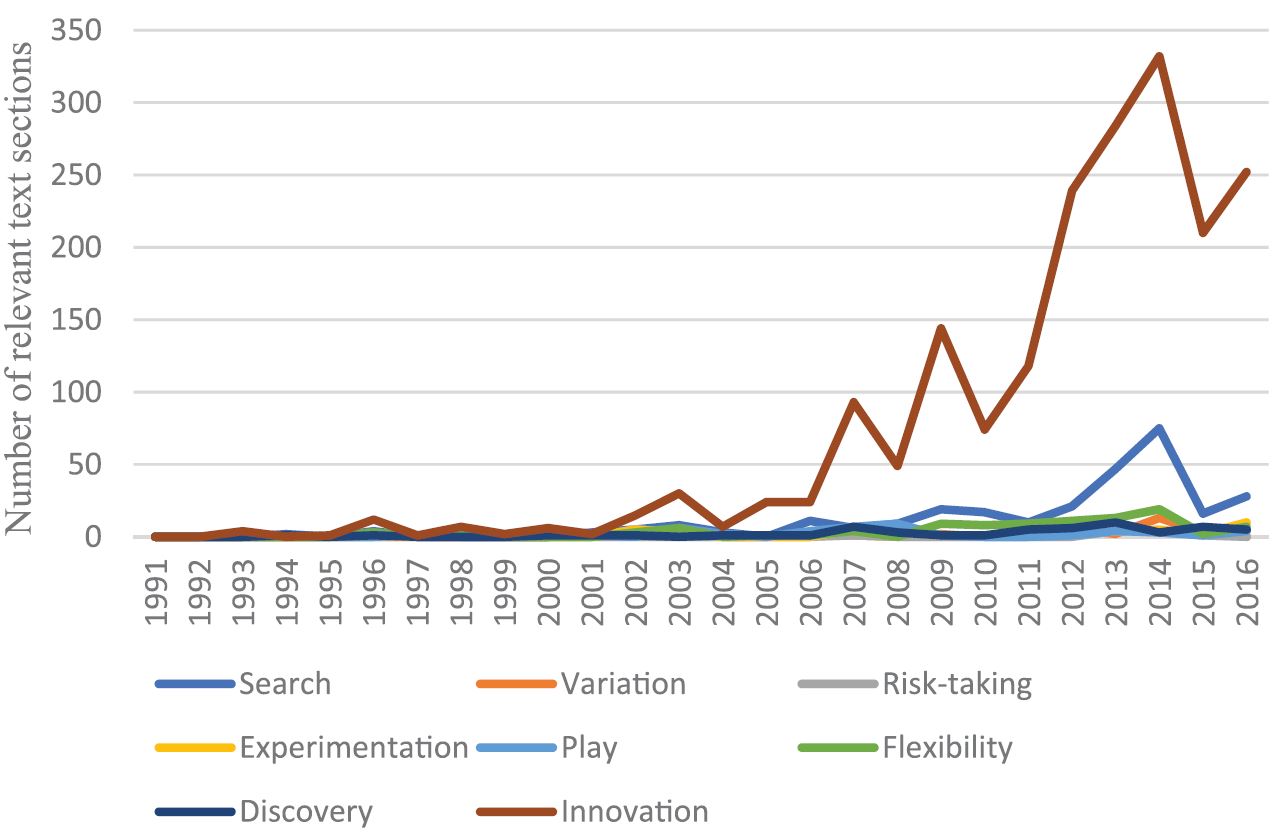

These features have been stressed in a recent review literature published in Strategic Organization (Wilden et al. 2018) among other evolutions of the constructs of exploration and exploitation following March’s seminal article. With an exhaustive dataset and data-mining methods, they have observed the evolution of the range of keywords initially proposed by March for exploration and exploitation (see Fig.1 and 2).

Exploration includes things captured by terms such as search, variation, risk taking, experimentation, play, flexibility, discovery, innovation.

Exploitation includes such things as refinement, choice, production, efficiency, selection, implementation, execution. (James G March 1991, 71)

The review points out the notion exploration has gained more attention: please note the difference in scale (y-axis), it is astonishing! It reinforces the importance of exploration to balance out biases of exploitation, but we should also keep in mind that exploitation should also be maintained to a certain extent (Birkinshaw and Gupta 2013). Co-existence is key to the performance and survival of the firm.

In (Wilden et al. 2018), they show the trade-off dilemma has drifted across several clusters of management literature with a recent emphasis on ambidexterity, organizational structure and performance (see section 2) and innovation management (see section 3) Several calls for future research are made to contribute to reconsider the organizational behaviour roots, extensiveness and micro-foundations of the constructs of exploration/exploitation, and their articulation with organizational boundaries (e.g. intra-organizational or across organizations).

Adaptive processes supporting organizational learning

The adaptive processes that are framed by given problems will call for numerous mechanisms ranging from “rational models of choice”, “theories of limited rationality”, “organizational learning and evolutionary models of organizational forms and technologies” (James G March 1991, 72). Within the information-processing paradigm, the notion of “search” is mobilized to understand to which extent decisions should be made to consider given alternatives and available information to organization action. As it is stressed, the decision model is quickly jeopardized with the observational capacity of the agent not being able to acknowledge new alternatives, sure thing principle1, or uncontrolled externalities:

The problem is complicated by the possibilities that new investment alternatives may appear, that probability distributions may not be stable, or that they may depend on the choices made by others (James G March 1991, 72).

This unobservability reinforces the limitation to adaptive process which should be optimized because of bounded rationality and theories of satisfying (Simon 1955) in addition to anchoring effects and other cognitive biases revealed by the works of Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman in their prospect theory (Kahneman and Tversky 1979; Tversky and Kahneman 1974). In the field of theories addressing the unknown, to go beyond available information and knowledge, theories of creativity with the support of cognitive psychology have emphasized similar phenomena: fixation effects (Smith, Ward, and Schumacher 1993; Ward 2007). But the bridge remains to be built between these two separate fields of research where theories and experimentations means do not yet synergize. The targets associated with the problem (pre-)framing define a reference frame to value learning and knowledge management. Organizational learning has stressed the importance of refining alternatives and inventing new ones. Exploration precedes or augments exploitation and will have antagonistic effects on the performance of decision-making (e.g. skills improvement to execute existing alternatives)(Levinthal and March 1981). This viewpoint on learning performance preconceives its criteria and the organizational ties between the exploration and exploitation regimes. It tends to hide the complexities associated with multi-scale phenomena at the individual, social and organizational levels as specified by J.March himself on balancing out the two regimes. Organizing an appropriate decision balancing exploration and exploitation becomes critical. In the tradition of adaptive process, the proposal from evolutionary theories introducing the notions of variation and selection is then quite seducing. J.March describes the purpose of these regimes and limitations by proposing the garbage-can decision process as a reservoir to protect from externalities and the unknown(Eisenhardt and Zbaracki 1992):

Effective selection among forms, routines, or practices is essential to survival, but so also is the generation of new alternative practices, particularly in a changing environment. (James G March 1991, 72)

The adaptation speed and the prior exploration/exploitation of appropriate practices will make a difference in the environment. Again, a structural or a sequential view of managing exploration and exploitation is suggested to take place at different levels: individual, organizational and social. For the organizational learning perspective, the interactions between individuals and the organization, and the competition for primacy between organizational (sub-)groups will contribute to the exploration/exploitation trade-off and vice-versa. The presented model is robust enough to cover several streams of literature and include some of the multi-scale complexity. Now, on the value of both regimes, J.March gives further indications on the necessity to separate them. Exploration is presented as a sacrifice and vulnerable because of overarching performance criteria derived from exploitation. The exploration valuation framework is exploitation-driven, as if on the same continuum:

Compared to returns from exploitation, return from exploration are systematically less certain, more remote in time, and organizational more distance from the locus of action and adaption. (James G March 1991, 73)

It reinforces the antagonistic effects of deciding of the allocation/division of resources to one of the regimes. The exploitation reference point also complexifies the understanding and efficiency of exploration during its refinement towards exploitation. Exploration is pictured as rather complex and fuzzy, highly uncertain and should be transformed into more systematic regime, like exploitation to perform better:

Reason inhibits foolishness; learning and imitation inhibit experimentation. This is not an accident but is a consequence of the temporal and spatial proximity of the effects of exploitation, as well as their precision and interconnectedness. (James G March 1991, 73)

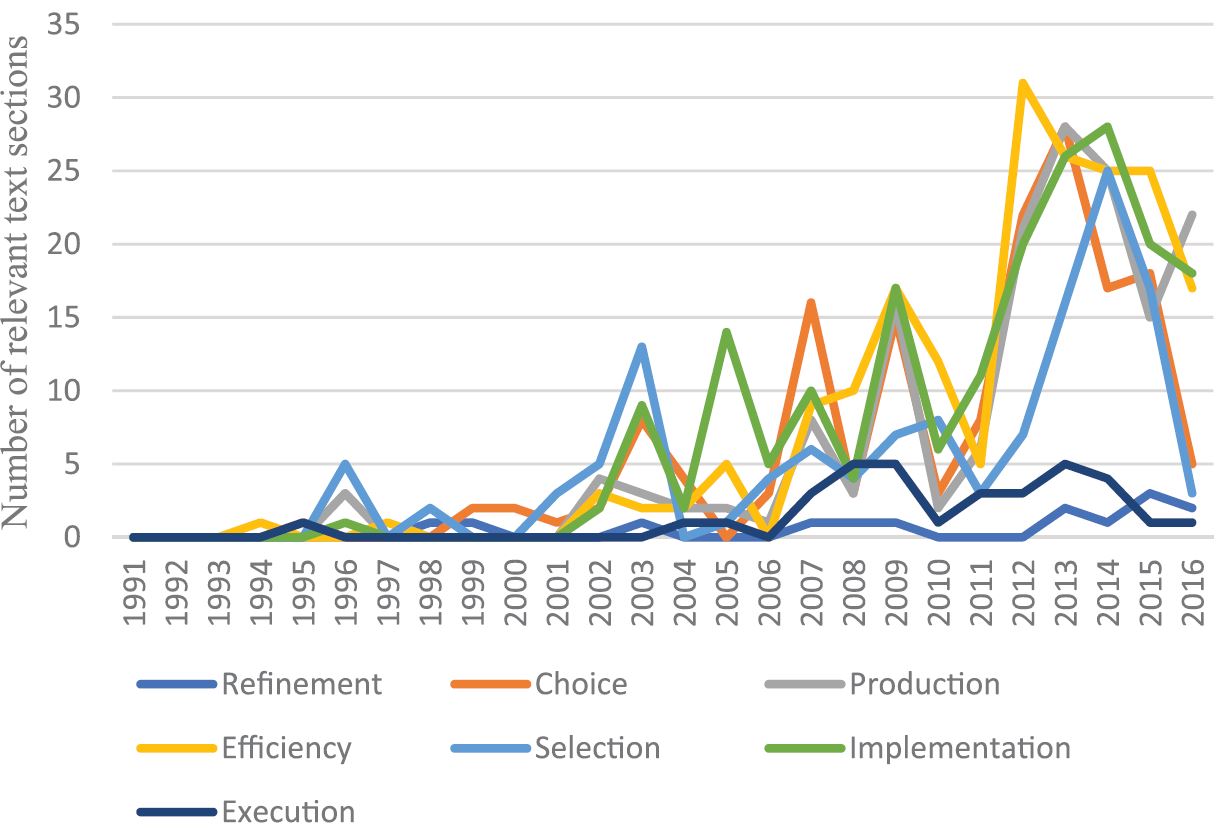

These views tend to emphasize paradoxically the orthogonality of exploration activities with respect to exploitation still triggering antagonistic effects for a given performance valuation reference. At the light of this model we could synthesize in the figure below:

Despite hiding several details of the model, the figure highlights the adaptation perspective and the learning required channelling the organization at the light of changes in the environment. It is a temporal representation, but it could also be picture in parallel, showing exploration oriented in certain directions usually blinded by exploitation.

We ask several questions echoing the limitations mentioned by J.March and the exhaustive literature review (Wilden et al. 2018) relative to the learning mechanisms and experimentation (discovery). The search-based model should enable reaching full rationality in opposition to its boundedness. As suggested in (James G March 1991), foolishness could be driving force. We must then clarify the behaviours, their categories with respect to problem-solving, search and decision-making.

Is it required to sustain the separation and balance between exploration/exploitation? How predictable are the discovery patterns? What are the spatial and temporal parameters to play with to balance out ambidexterity?

Learning with respect to foolishness, novelty and creative logics

In order to study learning mechanisms, James March along with other great researchers have extensively studied the sociology of organizations and some, if not most, have taken a close look at engineering activities (Dong, March, and Workiewicz 2017, 8). Engineering departments among other functions in the firm have created over decades design and engineering rules, set of established practices required to support product development and manufacturing. Engineering has been one of the major epicentre of novelty and also the baseline for daily exploitation. It is a place of tension and balance for exploration and exploitation regimes. Learning, imitation and forms of rationalization are deployed in such context to sustain exploitation regime. The knowledge management gravitates around and deals with the established rational model organizing collective action.

In an evolutionary perspective, efficiency can be improved with a better selection with respect to the production of such engineering organizations. Imitation is one sub-activity with the risk of converging on sub-optimal selections. Ways of controlling this convergence must be envisioned such as bringing novel knowledge, or in a network theory perspective, slightly disconnecting agents (Dong, March, and Workiewicz 2017, 8). Encouraging novelty becomes critical and J.March recalls that most novelties fail, leading to the promotion of the garbage-can decision model appropriate for unstable environment paired with a selection process. Benefits of others experimentation can also be drawn fostering vicarious learning (Riedl and Seidel 2016).

If you’re going to engineer an evolutionary process, you have to work on improving selection, and you have to work on improving novelty. (Dong, March, and Workiewicz 2017, 9)

Novelty is odd and uncertain, and this failure rate calls for some technologies of foolishness by opposition to exploitation behaviours ruled by established technologies of model-based rationality (March 2006; Dong, March, and Workiewicz 2017). Rational models have misspecified the organization of action due to numerous difficulties: uncertainty and the unexpected (Shackle 1949), causal complexity, preference ambiguity (Slovic 1995; Camerer, Loewenstein, and Rabin 2004) and strategic interaction (Pettigrew 1977; Eisenhardt and Zbaracki 1992; Chia 1994) just to name a few. So, other models with feedback means have developed to adapt continuously, to counteract myopic behaviours (Levinthal and March 1993) and surprise effects associated to incompleteness of previously mentioned models of rationality. Yet, these models may not reach a global optimum (Brehmer 1980; Carroll and Harrison 1994; Barron and Erev 2003).

These problem-based modelling approaches will frame the behaviour of the algorithm with certain boundaries and will not facilitate discovery of other domains. We can all picture a robot hitting a wall in a infinite loop with the hope to minimize the distance to the objective behind the wall despite having numerous sensors. Limitations of the agent bound its rationality because of numerous biases, but also the environment minors the performance of adaptive processes for being too complex, endogenous, subjective and contested (March 2006, 205). Experimentation is then required to put the robot in a position where novelty can be observed and gradually understood given pre-conceived rules. In that perspective, the novelty-search algorithms (Nguyen, Yosinski, and Clune 2015) applied for robots to adapt like animals in a resilience mode (Cully et al. 2015). This sets the frontier of problem-solving perspective and possible decisions, but leaves potential ones undiscovered due to bounded rationality.

The complexity rises when considering unusual experiences compared to existing knowledge basis and rational model as discussed in by Raghu Garud with a narrative perspective (Garud, Dunbar, and Bartel 2011). In the following extract, J.March plays with the edges of the model and the necessity to generate variety, but we can expect this generativity is limited to the landscape of bounded rationality and search:

The first central requirement of adaptation is a reproductive process that replicates successes. The attributes associated with survival need to be reproduced more reliably than the attributes that are not. The second central requirement of an adaptive process is that it generate variety. (March 2006, 205)

However, creative logics or generative processes in a broader and weaker sense (Epstein 1990, 1999) are required to bring variety to the process and add up to the existing knowledge (bounded and unbounded). But again, it goes beyond search/discovery and is rather associated with novelty and the reaching for the unknown. Exploration regime in its quest for variation, requires alternative mechanisms such as organizational slack, randomness, errors of adaptive process parameters and other mechanisms shifting the performance frontier with objectives derived from intuition of a leader. J.March makes then a case for foolishness and some kind of irrationality compared to the normative technologies of rationality established in the organization:

The designers of adaptive systems often proclaim a need for deliberately introducing more of them to supplement exploration. In their organizational manifestations, they advocate such things as foolishness, brainstorming, identity-based avoidance of the structures of consequences, devil’s advocacy, conflict, and weak memories (George, 1980; George and Stern, 2002; Sutton, 2002). They see potential advantages in organizational partitioning or cultural isolation, the creation of ideological, informational, intellectual, and emotional islands that inhibit convergence to a single world view (March, 2004). Whereas the mechanisms of exploitation involve connecting organizational behaviour to revealed reality and shared understandings, the recommended mechanisms of exploration involve deliberately weakening those connections. (March 2006, 207)

The numerous failures of rational models and their technologies are utopian (March 2006, 209):

It is argued that the link between rationality and conventional knowledge keeps rational technologies reliable but inhibits creative imagination. This characterization seems plausible, but it probably underestimates the potential contribution of rational technologies to foolishness and radical visions.

It encourages then the “heroism of foolishness” to support exploration and the use of technologies of rationality as a baseline to enhance exploration, and avoids pure irrationality. This last sentence blurs the boundaries of exploration and exploitation, let it be on the same continuum or in two orthogonal planes. It is a thin-wall domain defined here pushing the debate down the line of functional stupidity in organization (Alvesson and Spicer 2012), pure irrationality in (Brunsson 1982) and his subsequent works, or the role of opportunism and reliability (Lumineau and Verbeke 2016; Foss and Weber 2016).

Exploratory foolishness may sometimes be desirable, and technologies of rationality may be important sources of exploration; but the use of rational technologies in complex situations is unlikely to be sustained by the main events and processes of history. (March 2006, 211)

TeThe main question we can ask ourselves so far is how collective action should be organized in such domain of foolishness tangent to irrationality. And not managing appears almost clearly out of question due to the necessity to balancing the exploration regime to reach a global optimum with an enhanced adaptive process. We have reasons to worry as several authors have described the variety of learning behaviours (Garcias, Dalmasso, and Sardas 2015) at the light of learning/performing paradox (Smith and Lewis 2011); or even the systematic violation of management rules contributing to learning (Mangematin et al. 2011).

How do we articulate it with learning mechanisms and overall knowledge management? How could we turn such deviant behaviour into resources or at least start building dynamic capacities that will support innovation? Foolishness could contribute to unbounding individual and collective rationality, but perhaps also extend into the unknown. It remains unclear in the model and proposals made by J.March.xt

Shifting the performance frontier with innovation

The seminal paper of 1991 review (Wilden et al. 2018) addresses two research gaps related to the re-connection with behavioural roots and supporting capabilities required for exploration/exploitation (Wilden et al. 2018, 11):

How do behavioural tendencies of managers, such as the risk propensity of executives, relate to a firm’s ability to explore versus exploit? How do individual tendencies to explore versus exploit interact with environmental trends at the institution, industry, and country levels?

How do capabilities that support exploration and exploitation emerge and become embedded in organizational routines? Are there differences in the dynamic capabilities required for executing exploration versus exploitation? Which dynamic capabilities are required to overcome path dependencies in exploitation?

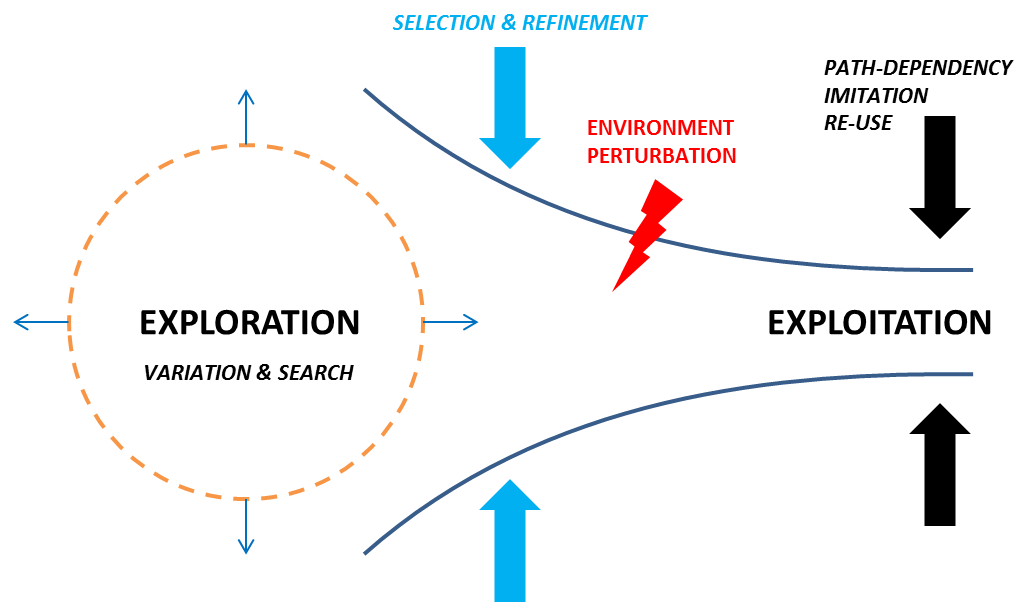

As we have stressed in the previous paragraphs, enhancing adaptive processes with novelty-driven processes supporting exploration may lead to numerous difficulties when trying to reconnect with exploitation regime: routines, rules and practices. The nature of exploration could otherwise fall in the domain of behaviours based on foolishness or rationality. In a behavioural perspective, it is crucial to understand what facilitates the allocation of resources for such activities. The underlying decision-making process must be clarified. Decisions are seen as trackers and reflections of the organizational life, and some of these are consigned into technologies of rationality. Agents in the firm develop associated routines that are rationally bounded and they consequently struggle to reach global optima on an objective Pareto front as pictured in the Fig.4. The previous subsection highlighted that agents are bounded in a biased knowledgeable space; exploration allows them to reach statistical optima on the Pareto front. Foolishness could perhaps contribute to the search vector for exploration, and it remains unclear if it contributes to generative processes broadly, into the unknown.

The tension created by exploration behaviours interfere with existing routines and rational models that could be expressed in terms of performance criteria delimiting the Pareto front: foolishness creates an exploitation oddity, an unusual experience (Garud, Dunbar, and Bartel 2011) that encourages to revisit the Pareto front definition or even the performance framing (x and y axes). Giovanni Gavetti (Gavetti 2012) pinpoints the ability to overcome focal behavioural bounds and reach for cognitively distant opportunities. Instead of paying attention to local collective action, he focuses on strategic leadership that would be able to manage such stretch. Such kind of system thinking elevated at the leadership level would encourage to revisit the strategic agency and governance of collective action. If one has attended J.March leadership classes or read (March and Weil 2003), one could find such behavioural leadership with fictional characters as Don Quixote: foolishness benefits his journey in some ways. The concept of behavioural strategy (Powell, Lovallo, and Fox 2011) proposes also to integrate the views of reductionist, pluralist and contextualist research. Despite the attractiveness of such consolidated and holistic construct, management requires to design concepts that explain collective action in organizations and at best would be actionable in practice. As suggested by the authors, it is as the crossroads we can build a comprehensive understanding.

So, in order to make a case for supportive capabilities required for exploration and exploitation, and combination of both, the behavioural perspective calls for some architectural design of adaptive systems for the organization as mentioned by J.March. The contribution of innovative practices, generative processes or how they are impacted remains to be clarified. It is a limitation of the problem-based view.

It also invites us to deeply understand the mechanisms of both exploration and exploitation and the associated dualism (Farjoun 2010). The paradoxical tension between regimes describes the adaptive system performance with an inverted U-shape between the degree of adaptiveness and the frequency of turbulence of the environment(Posen and Levinthal 2012). It prescribes then adjustments to the organization sustaining exploration and exploitation, and questions where and how arbitration should be made.

How should be structured the firm? How does leadership should design accordingly to support innovation and performance? What makes exploration and what makes the tension points when exploiting its outcomes?

Overall, we could say that we have two major models, one that would be structural and another one more processual. To organize collective action in the firm, it is also crucial to keep an eye on learning patterns, if exploration or exploitation contributes to core rigidities and incompetencies (Leonard-Barton 1992; Dougherty 1995).

Organizational ambidexterity: organizing unbounded problem-solving

In this section, we propose to cover the stream of literature focused on the approach to capture behavioural roots through organizational structure and design. Some hints of this research program can be found echoing portfolio project management or program management, and coordination & communication means deployed across the organization in relationship with learning mechanisms when competing for primacy (James G March 1991, 84):

Similarly, multiple, independent projects may have an advantage over a single, coordinated effort. The average result from independent projects is likely to be lower than that realized from a coordinated one, but their right-hand side variability can compensate for the reduced mean in a competition for primacy. The argument can be extended more generally to the effects of close collaboration or cooperative information exchange. Organizations that develop effective instruments of coordination and communication probably can be expected to do better (on average) than those that are more loosely coupled, and they also probably can be expected to become more reliable, less likely to deviate significantly from the mean of their performance distributions. The price of reliability, however, is a smaller chance of primacy among competitors.

The literature on organizational ambidexterity made the effort over several decades to capture the relationship between the constructs of exploration and exploitation with respect to several other observables: different level of analysis within the firm, influence of the environment, leadership and many more (Birkinshaw and Gupta 2013; O’Reilly and Tushman 2013). The numerous variables are usually studied through quantitative methodologies with surveys and databases. Correlations and patterns are then derived in relationship with the firm’s performance and innovation. Ways of organizing ambidexterity are typified with different impacts given a set of control variables centralizing most of debates in the field, and may have led to contradictions because of control variables.

Structural, sequential and contextual ambidexterity

The word “ambidexterity” preceded the seminal paper of (James G March 1991) in The ambidextrous organization: Designing dual structures for innovation (Duncan 1976). The concept was introduced for organization design to improve innovation capabilities. It makes an assumption on the innovation process seen in two sequential phases: initiation and implementation. Robert Duncan stresses the behavioural dimensions (resistance model mainly) and the decision-making associated to the innovation process. The so-called structural ambidexterity is designed to facilitate the management of ill-structured problems posed by innovation2. Given several behavioural features analysed, three conditional rules are prescribed for the organizational structure given the nature of innovation (uncertainty, radicality, need). Merging the literature of dynamic capabilities and organizational ambidexterity (O’Reilly and Tushman 2007) also emphasizes the importance of senior management to oversee the trade-offs of exploration/exploitation and the translation of sensing, seizing and reconfiguring (Teece 2007). Simultaneity is achieved by the structural organization of exploration and exploitation. The dynamic capabilities emerge from the contribution of senior management being able to oversee the overall reconfiguration of both regimes: a strategic intent with clear vision and values and the necessity to have ambidextrous leadership. This attraction for leadership and senior teams is given because of the risk of ambiguity of capabilities (O’Reilly and Tushman 2007, 190):

What is needed is the identification of specific senior team behaviours and organizational processes/routines that allow firms to manipulate resources into new value creating strategies. Ambidexterity as a dynamic capability is not itself a source of competitive advantage but facilitates new resource configurations that can offer a competitive advantage

This way of organizing is given for high strategic importance and operational leverage by opposition to other configurations: independent business unit, internalization/sub-contracting and spin-off. It is an answer to the ad-hoc/spin-out emerging business see in the innovator’s dilemma (Christensen 1997). The critical dimension of this stream is the contribution of a potential ambidextrous leadership from the top management and middle management (Benner and Tushman 2003, 2015). However, its nature and means of action are not specified. The sequential ambidexterity approaches the question of innovation and continuous change with. The sequential approach is more influenced by a continuous change perspective (Brown and Eisenhardt 1997). Brown and Eisenhardt bring the nuance of change in a more dynamic and continuous way contrasting with punctuated equilibrium. When considering the shift from exploration to exploitation (the opposite is rarely mentioned), they emphasize the importance of experimentation and light structure (semi-structure). It is a weaker form and blending the edges of the short burst of radical/discontinuous change in between long periods of incremental change3. Focusing on processes and systems allows to have an alternative approach to the structural dimension of ambidexterity:

Continuously changing organizations are likely to be complex adaptive systems with semi-structures that poise the organization on the edge of order and chaos and links in time that force simultaneous attention and linkage among past, present, and future. These organizations seem to grow over time through a series of sequenced steps, and they are associated with success in highly competitive, high-velocity environments.(Brown and Eisenhardt 1997, 32)

Contextual ambidexterity brought another modulation that tends to merge the structural dimension with the punctuated equilibrium by (Gibson and Birkinshaw 2004, 209):

contextual because it arises from features of its organizational context. Contextual ambidexterity is the behavioural capacity to simultaneously demonstrate alignment and adaptability across an entire business unit

The influence of context opens up the perspective on organizational ambidexterity by considering the boundary condition of the construct: environment dynamics. It also moves away from the trade-off allocation problem by simultaneously develop[ing] these capacities by aligning themselves around adaptability (Gibson and Birkinshaw 2004, 221). The interplay between adaptability and alignment is placed at the individual level, calling for paradoxes at the local level, in addition to support from senior management.

The three models described try to organize in different way the separation and balance between exploration and exploitation. The non-mutual conditioning is maintained: exploration and exploitation regimes happen in sequence, in parallel and at different levels and contexts.

Systematically, top management and its leadership is required to oversee and manage the balance, in addition to enabling some level of flexibility for transitioning dynamically. Yet, it does reveal the actual practice and implementation.

Limitations of organizational ambidexterity models

Authors have also highlighted the push from academic reviewers during their publishing process. Their qualitative study would indeed bring more depth to the construct of ambidexterity and separation between exploration/exploitation. They were encouraged to embrace the literature of organizational ambidexterity with (Birkinshaw and Gupta 2013, 288):

Interestingly, our original focus in this paper was not on ambidexterity per se. Our specific interest was in the tension between an organization’s capacities for alignment and adaptability, and in the role of organizational context to help it achieve an appropriate level of balance between the two. In developing the paper, we came across ambidexterity as one possible framing for our work, and we leaned heavily on Adler and colleagues (1999) in our theorizing. But it was actually the editor, Marshall Schminke, who had the bright idea to describe the phenomenon we observed as contextual ambidexterity, as distinct from the more structure-oriented approach to ambidexterity that Duncan (1976) and Tushman and O’Reilly (1996) had described.

In contrast to the amount of quantitative studies, the extensive literature reviews conducted by major authors (who have contributed with detailed qualitative or mixed studies (Benner and Tushman 2003; Gibson and Birkinshaw 2004)) in the field have called for further qualitative research and trying to surface underlying processes supporting ambidexterity in action (Birkinshaw and Gupta 2013, 332):

How they actually do this is seldom addressed in the research on ambidexterity but is at the core of the leadership challenge. What do the interfaces of the old and new need to look like? How can leaders manage the inevitable conflicts that arise? More qualitative and in-depth studies are required to answer these questions.

It is a call to reconnect with behavioural roots and to better specify the practice of exploration/exploitation and its management beyond pure trade-off as if they were on the same continuum. Quantitative studies have failed in specifying such phenomena:

Although the results are not completely consistent across studies, in general they confirm that structural ambidexterity consists of autonomous structural units for exploration and exploitation, targeted integration to leverage assets, an overarching vision to legitimate the need for exploration and exploitation, and leadership that is capable of managing the tensions associated with multiple organizational alignments (O’Reilly and Tushman 2013, 328)

At a high level of abstraction, it is easy to claim that firms shift structures between exploitative and exploratory modes—but what would this mean at ground level? Major structural transitions can be highly disruptive. What does it mean to go from exploitation to exploration, or the reverse? Here the research is not fine-grained enough to provide much insight.(O’Reilly and Tushman 2013, 327)

We know some organizations are more ambidextrous than others, but for this insight to be valuable we have to take a more detailed look at the way they make their decisions, who gets involved in those decisions, and how those decisions are implemented. For me, this is one of the areas where ambidexterity research has the most potential. There is, for example, some research looking at decision processes in top management teams (Smith & Tushman, 2005) and how executives embrace paradox (Andriopoulos & Lewis,2009), but I would like to see a lot more. (Birkinshaw and Gupta 2013, 293)

It is interesting to note the interest of leadership, which had raised as a reaction with respect to the awakening of the machines that Herbert Simon dreamed of. Stanley Stark (Stark 1963) in his review on creative leadership mentions the work Philippe Selznick’s of administrations through leadership (Selznick 1957), here is a stimulating extract:

Why did Professor Selznick write this particular essay? And why did he title it Leadership in Administration? Any reply to the first question should include, I believe, a statement to the following effect: he wrote it as an intuitivist supplement, corrective, or antithesis to the formalist essay that Herbert A. Simon titled Administrative behaviour. And any reply to the second question should include, I believe, a statement to the following effect: leadership in the old-fashioned sense, which stood so high with the intuitivist likes of Plato, Carlyle, and Weber, stands very low in the world of scientific empiricism; in Administrative behaviour… the word leadership itself cannot be found in the heading of a single chapter, chapter section, chapter subsection, or anywhere in the index. … My guess is that Professor Simon would wonder much, and that Professor Selznick would find it exceedingly difficult to satisfy him. But we must satisfy him if we are ever to convince him that at any given time the computer is not doing all the thinking that middle or upper managers do. For example, when he says that “we will have the technical capability, by 1985, to manage corporations by machine” (1960, p. 52), are we entitled to smugly retort, “Sure, but what about leading, creatively leading—a la Selznick—by machine?” if we cannot reach agreement on what Professor Selznick means? It is one thing to say to Professor Simon— “You’ve left creative leadership out of your social psychology and out of your machine” — and another to demonstrate that he has omitted a piece of reality.

Leadership is presented as a counterforce and extension of bounded rationality and technologies of organizing to reach optima. The decisions, the vision given by leadership remains to be specified. When comparing the structural and processual models (Benner and Tushman 2015; Birkinshaw and Gupta 2013), the contextual approach encourages to look at the business environment, not only at business unit level but in a more general perspective. With innovation management, organization may have to adapt in different ways, as it can shift the performance frontier of exploration and exploitation. Mary Benner suggests the innovation locus (Lakhani, Lifshitz-Assaf, and Tushman 2013) having shifted and being shaped in different ways (e.g. open innovation, community-based, exploratory partnerships), the ambidextrous organization should be revised as the adaptive process may no longer rely on models based on cost minimization, local search, hierarchy, power, control of contingencies, and extrinsic motivation (Benner and Tushman 2015, 508). It is interesting to note that this in-between concept, sheds a fresh light on fixations and path-dependency of some constructs that are showing limitations.

Similarly, in (Gupta, Smith, and Shalley 2006, 699), the system design with its engineering background on modularity (Henderson and Clark 1990) brings another way of contextualizing ambidexterity given the system architecture and innovation. Exploration activities can be conducted locally for a module, and exploitation can carry on in others as long as interfaces remain stable. The coupling between modules may also an obstacle to such approaches as explained in (Benner and Tushman 2003, 247).

Exploration and exploitation non-mutual conditioning may be then challenged by innovation practices and loci. The decision-making and managerial capacity (e.g. leadership) are not fully elucidated in the literature and would require fine-grained qualitative research.

Another way of considering the balancing of the dichotomy between exploration and exploitation, is to look at how the literature on paradoxes have nurtured a way of managing collective action (Smith and Lewis 2011). It would allow considering the antagonistic effects with different main performance criteria (generation of alternatives, and efficiency of choice).

Managing with paradoxes

The organizational ambidexterity literature with its organization adaptation for innovation and efficiency plays with translation of the underlying adaptive process articulated with exploration/exploitation. Researchers in the field have already stressed its limitations and calls for future research. Their synthesis calls for forms of ambidextrous leadership (O’Reilly and Tushman 2007) or at least a crucial involvement of senior management to oversee forms of structural/sequential/contextual ambidexterity. For a manager it will imply then allocating resources for a regime or the other in different ways in space and time. From a behavioural perspective, the manager will bear the paradoxes associated with the co-existence of these regimes or inversely will manage other individuals with such paradoxes (Papachroni, Heracleous, and Paroutis 2015).

Due to multiplicity of studies, their nature, their unit of analysis, the triggered paradoxes would be of different types when looking at the critical literature review of (Gupta, Smith, and Shalley 2006) in their special research forum. For instance, the definition of exploration and exploitation may depend on the unit of analysis chosen in the studies (multi-scale problem), the continuity or orthogonality of the two constructs, the system dimension opposed to organization and individual, interpersonal learning, tacit knowledge, inter-dependencies and local/distant search. They also specify that learning mechanisms associated with exploration or exploitation may of be different nature, as it was confirmed in (Garcias, Dalmasso, and Sardas 2015). Paradoxes then bring the promise of blending the dichotomy in a distributed way dependent on context. For instance, (Leonard-Barton 1992) reveals the paradox of new product development managers having to rely on existing core capabilities and still avoid associated core rigidities: e.g. values, skills and knowledge, managerial systems and technical systems. Paradoxes for project management were handled with different strategies associated with adaptive limitations: abandonment, recidivism, reorientation and isolation.

But paradoxes can also be embraced to manage a firm specially for senior management (Smith and Tushman 2005) who can overview the numerous organizational tensions (Smith and Lewis 2011). Teams arrangements, communication, leadership coaching contribute to adopting and managing the paradoxes in a dynamic equilibrium in order to avoid the fatality of cyclical patterns associated to paradoxes. For instance, (Smith and Lewis 2011, 392) proposes that some individuals with cognitive/behavioural complexity and emotional equanimity are likely to accept paradoxical tensions instead of defending. It is an invitation to dig into the constraints to better twist the paradoxes into managerial action. The unit of analysis to cope with organizational tensions may also be translated in different action registers as demonstrated in (O’Dwyer, Sweeney, and Cormican 2017) with project portfolio ambidexterity. CEOs are found to be using practices based on paradoxes to drive performance and innovation in firms (Fredberg 2014).

However, despite the attractiveness of paradox theory as an alternative to contingency approaches, the work of Linda Putnam in (Cunha and Putnam 2017) addresses the potential paradox of a success trap for this vigorous literature: the paradox of the paradox. Two issues retained our attention: the imprecision of the word and the paradox reversibility while being a problem/tool to manage. For our concern, as we question the possibility of actually organizing collective action through the paradoxes of ambidextrous tensions, its practice may become very diffuse and hard to grasp. Furthermore, the tensions created by these stretch goals (Sitkin et al. 2011) may be favoured in some organizational contexts but it also raises the question of the ambidextrous individual able to cope with such double binds (Holmqvist and Spicer 2013). The concept of double-bind thinking, introduced by Gregory Bateson (Bateson et al. 1956, 1963) may encourage some kind of schizophrenia or at least high level of stress among individuals subject to such organizational tensions. Others may be more successful. Such unbalanced performance for ambidextrous strategy and leadership encourages to dig a little further into the cognitive level.

For instance, in (Laureiro-Martínez et al. 2015), magnetic resonance imaging is performed on individuals to identify brain regions supporting the decision-making associated with exploration/exploitation and its trade-off. The findings include the awareness of the environment of decision-making, the influence of emotion and attention, the sequencing and switch of the two regimes, and learning mechanisms. The authors insist on the fact that their results do not encourage any form of selection and hiring but rather on the training.

Similarly, the contributions of the MIT’s System Thinking department’s director Peter Senge (Senge 1990) is suggested in the discussion of (Leonard-Barton 1992, 192). He calls in his paper for heuristics associated with leadership styles supporting a generative learning instead of adaptive learning. The leader could have new roles to support the tensions and organizational learning; leader as a designer, teacher and steward. The associated skills and management tools should then be developed, and would allow extending the model of adaptive learning with creation process in the continuity of coping mechanisms with a broader system thinking. This view of managerial action recalls also the works of (Starbuck 1983) considering organizations as action generators. So, instead of relying on the individual skills to cope with cognitive ambidexterity and associated strain, the focus could be shifted toward methods, practices and management technologies as well as organizational routines.

Finally, the paradox approach may leave us without clear means of understanding the practice of organizational ambidexterity, as it tends to distribute the paradox on multi-scale and phenomena fashion.

By following the lines suggested for future research in the ambidexterity literature reviews referenced previously, we propose to take a closer look at the decision-making process for exploration, exploitation and its trade-off. It may for instance document what is expected from leadership specially if they engage in generative practices shifting the frontiers of exploration and exploitation. So far, we have highlighted that macro-level analysis may be insufficient and rather too contingent, hence our need to explicit the underlying mechanisms.

Deciding to innovate: micro-foundations of ambidextrous organizations?

In this final section of the chapter, we propose to analyse the literature on decision-making supporting exploration and exploitation. First of all, the necessity of managing the adaptive process through exploration and exploitation was presented as a necessity to cope with externalities and sustainability. Along with the firm’s performance, innovation management has become the central focus of ambidexterity as it contributes to exploration/exploitation impact and trade-off.

The firm’s management decides then to innovate to feed the adaptive process with exploration regime which then requires to be transferred to exploitation purposes. We have stressed that these two regimes can structurally co-exist, be sequenced dynamically and more importantly may be shaped in different ways depending on the unit of analysis (organization, system and individual/cognitive). Relying on the decision-making process in a neo-Carnegie way (Gavetti, Levinthal, and Ocasio 2007), i.e. looping back with the behavioural roots of (James G March 1991), encourages to specify decision-making with respect to exploration, exploitation and its balance. Decisions are considered as legitimate unit of analysis. It is tracker of sociology of organizations (Crozier and Friedberg 1977; Pettigrew 1973; J. March 1991), perhaps even an artificial construct (Laroche 1995) for which we should perhaps prefer organizational action.

Uncertainty and the unknown

In the assumptions made by (James G March 1991), the problem space given to the firm to adapt to survive was set beforehand: exploration was a means to search for alternatives not considered by exploitation in the given problem space. However, the previous paragraphs on organizational ambidexterity and the focus on exploration preceding exploitation, gave several hints that the search could be more complex than the one originally defined by James March. Several keywords challenge what makes adaptiveness such as: unusual experiences, new locus of innovation with open innovation, environment awareness, system thinking, differences in learning mechanisms for exploration and exploitation and the adjective generative.

Originally, the problem space involved statistical and optimization dimensions for the decision-maker. In other words, statistical learning and subjective beliefs that could be modelled in terms of probabilities. We are in the realm of risk-taking and uncertainty. The consequences of decisions are known but the probability of happening is not known. The search-model of exploration consists in looking at other consequences and decisions to enlighten the decision-maker by having the global picture of the problem instead of being bounded. By referring again to earlier definitions (Levinthal and March 1993, 105), the research developments suggest that exploration encourages to specify the regime of generation or generativity of new knowledge in its broadest sense: [exploration] the pursuit of new knowledge, of things that might come to be known and [exploitation] the use and development of things already known.

If new knowledge is generated by experiences (changing environment) or deliberate experimentation and action, the rational choice theory reference4 is no longer fully valid as we force the set of possibilities to become larger and potentially reconfigured (Hey 1983). We enter the realm of the unknown or unknowledge as suggested by G.L.S Shackle (Shackle 1949; Frowen 1990).

In the field of operations research, (Ozdemir and Saaty 2006) proposes to add a variable labelled “Unknown” with uncertain probability; the model can then be used for decision-making and take into account the perception of the unknown. In other words, the “other” states of the universe of probabilities are integrated, so it means really re-examine the full extent of the theoretical, objective and unbounded problem by opposition to the rationally bounded one.

It is not an actual theorization of the Unknown as we have defined it: states of nature and decisions that we are fully unaware of it but that only action can reveal. The dynamic dimension of decision-making naturally updates the sets of choices, consequences, and utility function but decision theories rarely focus on this feature because of potential problems of dynamic consistency, modelling complexity and preference revelation given choices made (Machina 1989; Chabris, Laibson, and Schuldt 2006).

The timing issue dragging behaviours such as patience and impulsivity are not really our concern despite being also part of life in organizations. We are rather interested in what could be willingly generated in a static frame: changing belief, new decision.

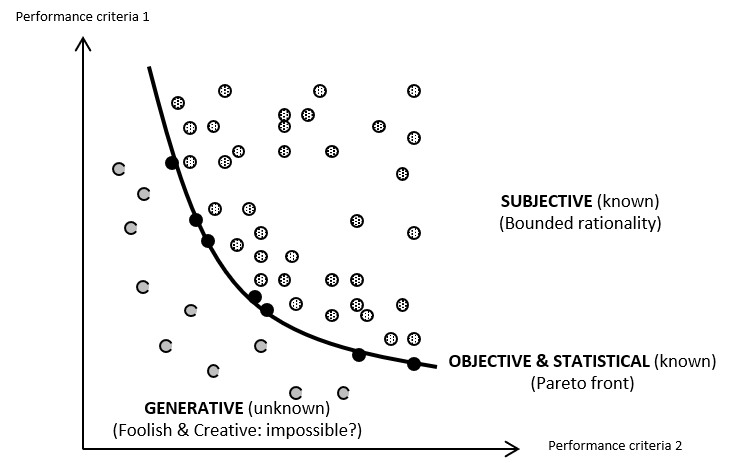

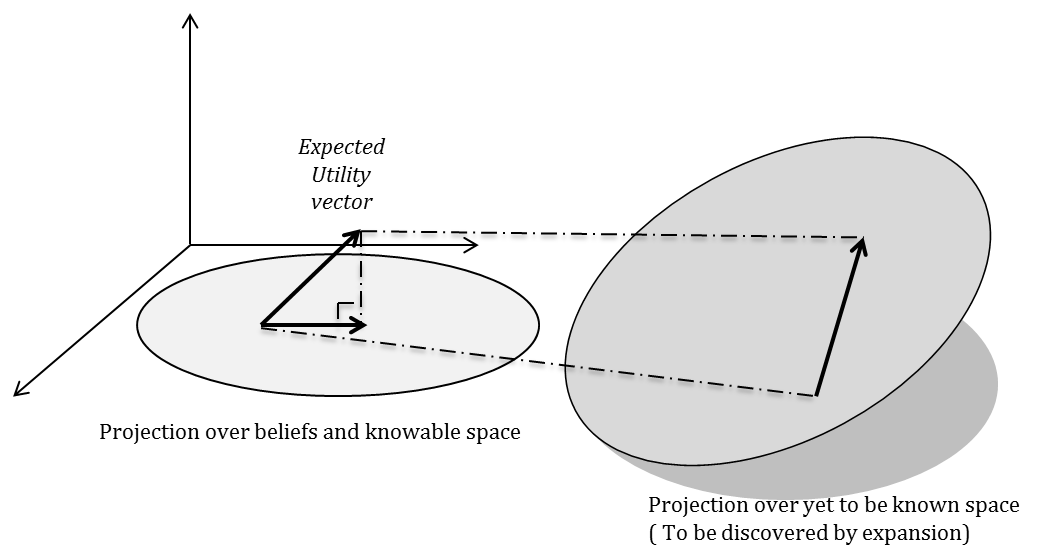

Coming from a decision problem to another invites us to consider the generative function that allows the transfer between the two. It is an expansive projection by opposition to traditional projection reducing the scope (se Fig.5 below). In other words, it is not reducing uncertainty over time with numerous means of actions (Sommer, Loch, and Pich 2008). Instead, shifting from a problem to another increases uncertainty temporarily before further experimentations can be performed (e.g. testing). Likewise, the need-solution pairs developed in (Hippel and Krogh 2016), stresses the existence and discovery of new problems and opens a field for how to behave in such unknown landscape.

Such behaviour has been studied in cognitive psychology where the avoidance and search for the unknown can be channelled through the curiosity and regret (Dijk and Zeelenberg 2007). Based on information-gap theory (Ben-Haim 2006), it proposes a first step to consider known unknowns (Rumsfeld 2002 a, 2002 b), but double unknowns again are not part of the equation. The case of Black Swans (Taleb 2007) and the types of uncertainties associated with knowledge categories can bring a new light on the decision-making process (Faulkner, Feduzi, and Runde 2017). It helps defining with more clarity the boundary conditions of expected-utility theories which presuppose what is known and uncertain, compared to other theories such as non-expected utility ones (Machina 2010, 1989; Starmer 2000; Quiggin 2014). But, they still lack in sensing and seizing double unknowns despite revealing a number of interesting behavioural features that could contribute to the generation of new knowledge and choices. They refer to phenomena such as: preferences reversal, dynamic inconsistency, anticipation, optimism/pessimism, regret, that call for mathematical models that are not additive in the classical sense.5

The literature on decision-making with respect to exploration and exploitation, stresses the importance of generative learning and the frontier with the unknown.

Decisions and search of new alternatives can be of different nature, hence changing the nature of exploration and consequently of future exploitation. We must study in more detail the edges of the Pareto front and its potential crossing.

We propose then to study the interplay between search relieving bounded rationality (known) and generation of new knowledge reconfiguring problem formulation and solving (unknown).

Generative processes: creativity, engineering and design

Exploration distinguishes itself from exploitation by introducing a way of reasoning that is quite challenging for it. We propose to take a closer look at the generative phenomenon and how it is translated in practice to support exploration.

The idea of generating alternatives with a background of theory of creativity was introduced by the works of Robert Epstein. He proposed a weaker definition of creativity, namely generativity, to study how animals would engage in creative problem solving (Epstein et al. 1984). With his colleagues, he put forward that pigeons would engage in actions helping them to gain insight to solve the problem in a novel way. In that sense, we are close to the novelty-search algorithm mentioned previously (Nguyen, Yosinski, and Clune 2015; Cully et al. 2015). Generativity is the distinctive feature of design theory and practices. Designers engage in jotting, sketching, drawing, writing and speaking (Brun, Le Masson, and Weil 2016; Goldschmidt 1991; Ferguson 1992; Goel 1995). All of the tasks, that could also be seen as micro-decisions, contribute to idea generation.

With the emergence of brainstorming (Osborn and Rona 1959) coming from advertisement and the large contributions of cognitive and group psychology (Guilford 1967; Amabile et al. 1996) numerous managerial practices have been prescribed to support innovation in organizations (Amabile 1988). Our aim is not to make an exhaustive survey of available practices, but rather to identify the performance discriminants of generative processes supporting exploration and eventually efficiency exploitation. It will help us in better understanding what causes and follows a generative process, i.e. the “operator” that supports the discovery of new knowledge, that allows making our way through the unknown.

Design Thinking

In the last two-three decades, Design Thinking has become the centre of attention for numerous companies and consultancy firms (IDEO, Continuum). Looking back at its origins at Stanford’s School of Engineering, the director of Product Design (Faste 1994) stresses the need to teach young engineers to ambidextrous thinking:

The gestation of Ambidextrous Thinking has occurred both in a College of Visual and Performing Arts (Syracuse University) and a School of Engineering (Stanford University). Thinking in the former setting is often characterized as being soft and fuzzy, in the latter, cold and hard. These characterizations are impediments to understanding the nature of design process. The central mission of Ambidextrous Thinking is simply to acquaint engineering students with the full range of their human potential in order to encourage a more balanced and potent approach to problem solving. In so doing it demonstrates the important connections between these seeming opposites.

Several techniques are taught to students to deal with reasoning trespassing traditional analytical thinking:

Many of the techniques pioneered in this class are showing up in local research and design firms. Examples include mind-mapping, scenario improvisation and story-boarding. I believe there is more to this than the efficacy of the techniques students are bringing with them to the work place. With the introduction of electronics, increasing numbers of products are as much about the design of desired behaviours as they are with the delivery of utilitarian function. Sole reliance on analytical skills will not guarantee engineering success in the increasingly consumer oriented marketplace, nor will it help engineers process the overwhelming amount of information that they will be facing in their careers

Design Thinking has evolved in a methodological toolbox to democratize design to all individuals in a wide variety of contexts (firm, public institutions, associations and classrooms). It tends to challenge design as a profession (Kimbell 2011, 2012). However, its underlying generative processes can be coded to explain engineering in its globality (Mabogunje, Sonalkar, and Leifer 2016). It is powerful and can be hosted in firms to stimulate new product development at its frond end, but still raises the question of its performance (Schmiedgen et al. 2016). The task is rather complex as performance criteria considered for tame problems (in exploitation) are ill-suited for the wicked problems at stake (Rittel and Webber 1973; Buchanan 1992).

Focusing on the generative phenomenon per se, or in its simplest form “idea generation” (fluency), we should pay attention closely enough to what supports generativity in the design (thinking) process. For instance, (Sonalkar, Mabogunje, and Leifer 2013) introduced the Interaction Dynamics Notation to track “concept generation” and a comparison is made against Linkography (Goldschmidt 2014). Their research method stresses how crucial the expression of an idea is for the individual and inter-personal relations engaged in the design process. Works in cognitive psychology from (Smith, Ward, and Schumacher 1993; Ward 2007, 1994) have also stressed the decisiveness of knowledge categories to stimulate idea generation with the notion of fixation effects It creates a potential performance reference point for exploration. Such anchoring could be associated with boundedness, and requiring a search for other alternative, but also the limitations of search in a given problem space.

Design theories and design engineering: rules and fixations

Other approaches originating also from an engineering background have developed theories to frame the design reasoning in different universities across the globe under the umbrella of the Design Society. Currently, C-K theory (Hatchuel and Weil 2009) has managed to be general enough to explain other design theories and practices (Le Masson, Dorst, and Subrahamanian 2013; Agogué and Kazakçı 2014; Hatchuel, Le Masson, and Weil 2011). Considering design theories, with respect to creativity and innovation management (Le Masson, Weil, and Hatchuel 2017) also allows extending design theories domains where engineering and product design have been lacking (Eppinger 2011). So using design theories as a reference tool to measure generativity could be an appropriate instrument. Tracking design fixations relating to cognitive fixation effects was studied and modelled with C-K theory (Agogué, Le Masson, and Robinson 2012; Le Masson, Hatchuel, and Weil 2011; Houdé 1997).

The capacity to avoid fixations, potential traps associated with exploitation, associated routines, and heuristics appears as a crucial performance criteria of the generative processes supporting exploration. The power to defixate will be hold as key to value the richness, usefulness of exploration.

However, this performance may be seen as self-destructive or antithetical for exploitation. They may generate concepts and knowledge pushing decision-making to its limits and complicating learning mechanisms. Indeed, these generative processes may be seen as upstream processes, in the fuzzy front end (Brown and Katz 2011; Leifer and Steinert 2011) for design thinking, as it is the case also for innovative design practices by opposition to systematic design (Pahl and Beitz 2007) or rule-based design (Le Masson, Hatchuel, and Weil 2011).

Returning to home base by avoiding spin-off and fully ad-hoc devices mentioned in organizational ambidexterity encourages to think of how beliefs and utility (value) are managed to reach the end decision to innovate. The organizational learning calls for a third loop of learning (Leifer and Steinert 2011), or a meta-learning (Lei, Hitt, and Bettis 1996) extending the single/double-loop learning (Levitt and March 1988; Argyris and Schön 1978). Both favour reconfiguring the system in a wider perspective. It would not be incrementally, nor just between elements, but rather with underlying categories and descriptors.

In a tangent approach and still without considering the screening issue, researchers in design management have largely insisted on the vitality of the creation of meaning to support innovation management through design practice (Verganti and Dell’Era 2014). In that perspective, we rally the notion of dynamic punctuated equilibrium (Brown and Eisenhardt 1997), where the exploitation is relieved from strictness to explore with a semi-structure through different means of experimenting. The necessity of a temporal or structural handover is blended in the process. This “objective” of meaning and stabilization is also clearly described in the works of Carliss Baldwin with the design rules (Baldwin and Clark 2000). Rules can then be used as criteria for decisions, and organize design activities around these.

Homo Faber/Deux ex machina: Designing mutations

In a perhaps slightly outdated practice (Kesselring, Fritz (VDI 1942) stemming from an earlier version of systematic design (Pahl and Beitz 2007), German engineers looked at decision-making for product design where the design process is punctuated by technical and economical evaluation enhanced by research and idea generation and ad-hoc decisions. He proposes that it is a means of developing products and also coming up with technical mutations. The biological analogy is derived from evolutionary theories:

Finally, the following interesting analogy between the divine act of creation in nature and the human act of creation in the technology should be noted. In both cases, from time to time, there is a discontinuity, apparently without a demonstrable relation to what has gone before, something new. We call this a “biological mutation” and mean by it the realization of a divine idea, the other: “technical mutation”, meaning the sudden appearance and the first realization of a human idea. Just as it is one of the great tasks of biology to investigate the emergence of mutations in their field, so for us it must be one of the top guidelines to explore the preconditions for the emergence of ideas.6

In his paper written during his time at Siemens, he does not develop the importance of models design to value ideas’ technical/economical dimensions contributing to the decision process. The idea remains seductive, as he departs from a classical evolutionary perspective by the fact he intends to generate mutations. The origin of the mutation, and its actual process remains to be specified.

So far, we have insisted on the necessity to have generative processes supporting exploration in the sense they should generate alternatives. Fluency is key.

Second, the ability to defixate is important to value alternatives differing from those at reach in exploitation regime. Methods and models are required to support such process that is not as straightforward due to biases and heuristics.

Third, a corollary, to counter isolation of exploration (James G March 1991), generative processes should look at avoiding concepts being a wildcard in the game of exploration/exploitation trade-off. Specially for decision-making and the meaning creation as the beliefs and utilities may be twisted depending on the course of action and life of the concept in the firm.

Furthermore, we see that exploration can be of two different orders and interacting with exploitation in the realm of what is known but also with the unknown. Such interplay brings new complexities for decision-making due to problem-formulation. It raises also new questions for organizational learning and adaptation.

Organizing ambidexterity through interactions

Managing generative processes, managing design and its impact on exploitation routines (problem-solving, decision-making) requires overcoming the core performances of fluency and defixation. In (James G March 1991; Dong, March, and Workiewicz 2017), he advocated that the volume of ideas, technologies, ventures is a necessity in the spirit of technologies of foolishness without explaining the tension and selection between explored and exploited alternatives. So far, we have developed through the literature the necessity to manage the trade-off of exploration/exploitation, and each regime individually, with an emphasis that the trick lies in exploration and its transition. Generative processes would be the engine of exploration and simultaneously complexify its articulation with exploitation. We have specified that deciding to innovate implies revisiting the decision-making process. How could this distance be reduced? The question becomes then how to manage generativity and how to manage design.

Managing design

The role of the leader as a designer had already been introduced (Senge 1990), and recent works have also stressed that managers should not be only focused on decision-making but perhaps should be designers (Boland and Collopy 2004). If the firm is fully design-oriented do we avoid decisions? Either way, collective action will be organized in some way and will contribute to the purpose of the firm.

The locus of Design in the firm and interactions with other departments is rather critical to understand its impact. When surveying the role of industrial design in British firms (Gorb and Dumas 1987), Angela Dumas in her years at the London Business School’s Centre for Design Management, revisiting the notion of design given by Simon’s definition where Design departs from Science: Everyone who designs devises a course of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones (Simon 1996). Instead of only focusing the artificial dimension of design, i.e. development of an artefact, A.Dumas and P.Gorb insist on the system of artefacts and how individuals interact with such system. Design’s definition is extended to take into account the managerial and behavioural dimensions:

a course of action for the development of an artefact or a system of artefacts; including the series of organizational activities required to achieve that development

They show that design occurs in a silent form already across the firm despite not being recognized as such: professional designers, design department etc. If design exists in a diffuse way across, so it means that we could have a way to articulate the generative processes’ outputs with existing routines as individuals engage in design in their own way and domain. For Design Thinking practice, several tools used that fall in the categories of need-finding, idea generation and idea testing (Seidel and Fixson 2013) will bring limitations and support other practices. Anyhow, several ad-hoc management tools and practices have to be implemented to link this exploration practice with product development for instance (Beyhl, Berg, and Giese 2014; Beyhl and Giese 2015).

The role of prototyping appears crucial to implement Design Thinking (Holloway 2009; Stigliani and Ravasi 2012). Klaus Krippendorff largely contributed to the importance of artefacts and the associated semantic turn (Krippendorff 1989). In a similar way, Angela Dumas (Dumas 1994) stressed the importance of relying and building totems through metaphor-making in product development as it can engage the ‘silent designers’ (Dumas and Mintzberg 1989, 1991) to revisit the decision-making process altogether around these totems. Based on a case on shoe design, here is a totem example:

The result is a set of slides, caricatures, and words that represents the product family - this is the totem. Most of the shoe manufacturer’s teams produced totems consisting of a phrase and a slide, or a slide and a caricature. While totems can include several slides, caricatures, and phrases, it is important that they combine to form a simple and memorable metaphor, and this is often best achieved with just one or two phrases and images.

Referring to totems call for a (too) short digression on the works of Emile Durkheim (Durkheim 1915). He reveals how religion is social phenomenon, pushing aside the traditional sacred dimension on the back seat, and insisting rather on the collective consciousness built around totems. If we allowed us such detour, it is because of the works of André Orléan on the notion of “value” in economics (Orléan 2011). He proposes that the value should not be considered as a substance in itself driven by work value and subjective utility in economics models, but rather stemming from the market economy where producers and buyers (exchangers) meet to trade goods. So it is the circulation that makes value and meaning.

Managing meaning and making sense of the unknown

These notions of meaning and value around the unknown shaped by generative processes encourage to manage generativity through its social dimension that crystallizes around the decision-making, the learning, the sharing and the diffusion.

One could then engage design in the firm through the cultural impact (Buchanan 2015) by supposing that design is more mindset enhancing daily concerns. The trick is also to reach out for all silent designers if we follow the spirit of democratizing design and creativity. Design Thinking has proposed that the empathy building for users could support a design thinking culture within the firm (Elsbach and Stigliani 2018). Based on the literature on organizational routines, the trick is also to be able to frame Design Thinking within the firm. It appears crucial (Carlgren, Rauth, and Elmquist 2016) as it can become in many different forms and relying on different set of tools. Several themes can be identified: User focus, Problem framing, Visualization, Experimentation and Diversity. They all involve principles, practices and mindsets. The latter will contribute to its culture which can be even more enforced through management education and wide training programs (Dunne and Martin 2006; Martin 2009). Yet, reaching institutionalization may not be the only key to let innovative design develop and be sustainable in the firm due to key players: silent designers (Dumas and Mintzberg 1989). They are those who engage in some generative processes on a daily basis with, for, or against rational-based technologies (management technologies, routines, communication channels, meetings, gates etc.).

Furthermore, making decisions and their formalization may be not key in early phases of generativity because of the lack of shared understanding and belief. The middle-ground between generated concepts and social system is the place where they simultaneously shape each other (Akrich et al. 2002). Individual will gradually gain interest (intéressement) that can eventually sustain innovation management, without focusing on the rationality of decisions [(Mintzberg and Westley 2001)]7. This analytical lens leads to how sensemaking (Weick, Sutcliffe, and Obstfeld 2005) can contribute to managing the unknown.

In the case of product innovation, some works have stressed the sensemaking for product innovation showing that its system have different dynamic compared with non-innovative contexts (Dougherty et al. 2000). For instance, they stress that tensions are created in through different themes: framing of knowledge (new) links, tensions across product/business/strategy ventilating sense and knowledge across all levels of the firm. Making decisions on innovation would be a fallacy where people actually look for approval and rather building sense interactively (Christiansen and Varnes 2007). This viewpoint insists that innovation management should create the means to support such interactionist action to sustain learning mechanisms and handling novelty from exploration to exploitation. In other words, the creation of meaning, the sense-making and associated learning triggered by generative practices rely on a certain ecology of generativity. We derive the notion from the ecology of creativity described in (Cohendet, Grandadam, and Simon 2009; Harrington 1990) but also the case of managing technical experts in science-based firms revisiting the concept of epistemic communities by creating diversity (proto-epistemic societies) in (Cabanes 2017).

In (Stigliani and Ravasi 2012), they refer to prospective models of sensemaking driven by design thinking practice (Continuum agency) but unfortunately it considers only the design process without calling for the generativity for the client or the designed object for end-users. We can actually question the usefulness as the CEO of Continuum stated in (Lockwood 2010, 20):

Q:I would think that afterward they might fall back to their more analytical thought processes. A: Oh, that’s absolutely true. But it’s progress, even if it’s like taking two steps forward and one step back. In some cases, they may even have a natural tendency toward design thinking, but it has been sup- pressed because of the way things are traditionally done in corporations. Q:I wonder if there is any concrete way to evaluate the prevalence of design thinking or design as a competitive strategy in to- day’s organizations. Do you have any recommendations for how we might assess this? A:That’s a great question. I don’t know how you would measure it, though. You know, that’s kind of the essence of the value of design thinking: You start to value things you just can’t measure. If you try to measure what you can’t measure…

Undoubtedly, generative processes rely on several practices, heuristics and learning mechanisms that include a social dimension to create meaning, make sense, that could perhaps in the end lead to decisions once interest and beliefs are settled. A sister approach is also addressed with the sensemaking perspective in a crisis mode (Berthod and Müller-seitz 2016) with the notion of managing the unexpected (Weick 2011) and highly-resilient organizations (Sutcliffe and Christianson 2012). But it is unfortunately a case for high uncertainty and extreme level of adaptiveness.

Finally, we have seen that there are ways of explaining how the unknown could be used as a driver to create meaning and gradually make sense of the novelty. Totem, metaphors, desirable futures can used to organize innovation. But still, by being “pre-decision” it avoids the decision-making and some behavioural dimensions of exploitation. Inversely, if were to follow this interactionist perspective we struggle to identify the handles to manage exploration.

What are the useful, necessary articulations and interdependencies to work on? Should we only rely on generating enough and hope that some will go through this ecology of generativity?

This probe onto decision-making for innovation, playing on the balance and performance of exploration and exploitation tends to reinforce the dichotomy between the two. It shows from the organizational adaptation and learning perspective that generative processes can occur upstream or in a distributed way. In any case, they emphasize the antagonistic effects of exploration and exploitation. The modes of collective action can take different shapes (linear and/or interactive), but still rely on managerial personae to separate and balance both regimes.

Chapter conclusion: limiting assumptions on the extension of generative processes