Chapter 9 - Organizing and testing decisional ambidexterity

The more any quantitative social indicator is used for social decision-making, the more subject it will be to corruption pressures and the more apt it will be to distort and corrupt the social processes it is intended to monitor. (Campbell 1979, 85) Donald T. Campbell

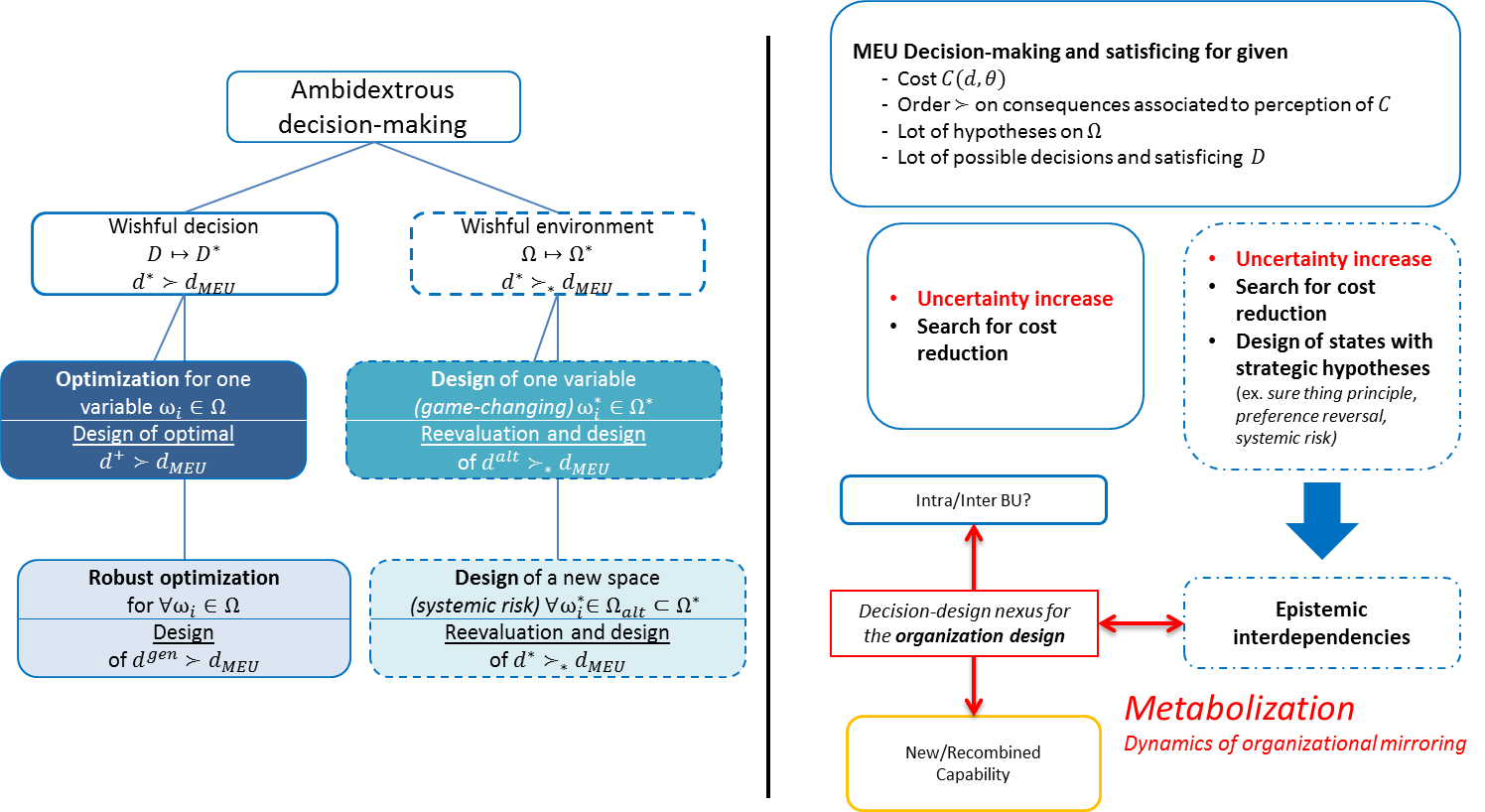

In this second modelling chapter, we have to fill in the gaps for the model requirements we have defined for ourselves at the end of the anomaly detection chapter. The definition and specification of decisional ambidexterity in the previous chapter addressed some of the descriptors used earlier in our methodological approach. The organizational dimension was not fully discussed as we have mainly stressed the decision-designing to revisit the mutual conditioning between exploration and exploitation in order to start anew with organizational ambidexterity.

Recalling our review on project based management, interactionism and organization design, we will build upon limitations previously identified to complete our decisional ambidexterity model.

Beyond dichotomy: simultaneity

The different cases presented in the anomaly detection chapter revealed several tensions associated with the encapsulation of generative processes and their potential free-floating across organizations (Lenfle 2016). Decisional ambidexterity allows focusing on the micro-foundations of exploration/exploitation dichotomy: revisiting the decision-making by considering decision-design permits touching upon one of the key aspects of coordination and collective action organizing for innovation. The way action is engaged, the way decisions are made, and the way organization members network (Christiansen and Varnes 2007) can be captured through the decision-design in the C-K formalism.

The transformation, due to exploration, or the one faced in exploitation because of the unexpected, can imply an active role for decision-designers as they play on states of nature, the degrees of beliefs and the cost functions will be redefined. Consequently, at the project management level depending on the framing imposed to the decision-design and the underlying engineering brief, the interdependencies can be controlled or even avoided depending on the aimed independence level. The latter will contribute to the innovation potential of attraction at the organizational level: how business units will host, support, redesign their organizations or recombine their capabilities for such projects. As we remember, we are not interested in spin-off and other ad-hoc phenomena, we want the organization to regenerate itself “within its boundaries” by relying on its organizational metabolism.

Project management: product or organizational change?

Uncertainty/Unknown buffer to manage the ecosystem relationship

We had specified that the project-based organization was probably an efficient way of organizing the firm to face uncertainties. Projects can be seen as uncertainty buffers (Davies, Manning, and Söderlund 2018, 971):

integrate cross-functional resources and knowledge to cope with high uncertainty, complexity and change

However, we remember that when pushing this form into the unknown reveals several difficulties that are exacerbated in cases where the organization’s identity and boundaries are tied by market rigidities tightly linked to product engineering. Zodiac Aerospace is a proper example of such pattern.

The Icing Conditions Detection case was a vehicle to shape the unknown, an example of decisional ambidexterity, by playing on preferences’ order to value the unknown and manage the ecosystem. It built its own autonomy through public funding and legitimation with key industrial players. It allowed more flexibility compared to a traditional exploration that would have been fully hosted by an engineering or product development department with a functional form. Just like in the two other cases analysed previously, the projects were sponsored by middle and top management, sometimes even having a key isolated position from other routines. It gives freedom to operate.

The relationship to the environment and the ways projects engage with it relocates organizational adaptation and learning at the project level in a temporary organization, whereas organizational ambidexterity would have a tendency to materialise it in a permanent organization.

A vehicle for change: which manageable parameters?

The necessity of change appears as the interdependencies have shifted (Stan and Puranam 2017). It is deep down what makes management a reality. Organizing collective action is necessary only at the wake of novelty forcing a transformational experience. If the project brings some novelty through decisional ambidexterity it will rely on existing interdependencies (exploitation) to generate new alternatives. The mutual conditioning is required to surface and manage interdependencies.

When discussing the interface between design and manufacturing activities in (Adler 1995), the author targets the cruciality of coordination mechanisms around interdependencies defined by the new product development. Mutual adjustment and interaction models will vary depending on the analysability of product/process fit. It is key to be able to reflect the organizational change required for the engineering interdependencies as they will be directly used as springboards to articulate the mutual conditioning between exploration and exploitation.

As new decisions are designed along projects trajectories, they can phase out compared to established organizations. It forces to conform the project to the host and permanent organization. It can even (implicitly) consider that the host or integrating BU would not change.

In the Design Thinking projects, as well as the BC seat platform, when transferring the designed products and made decisions, they faced the exploitation regime in permanent organizations with established engineering design rules. The learning and organizational change was not on the menu of the project nor handover with the redesign of decision-making.

For instance, ADT did try to refine designs, but it was rather an optimization effort instead of playing on states of nature to envision the required change in engineering constraints, product interfaces, standards, regulations, market segmentation, business models, etc. For the seat platform, the learning and design rules evolution came after relying on late and repeated mechanical tests which confirmed previously discussed but underestimated numerical simulations.

Mirroring hypothesis: a static view

We had identified in the literature the mirroring hypothesis (Colfer and Baldwin 2016). We could a priori use decisional ambidexterity in exploration project management that considers existing product design architecture as a starting point. It would involve a number of design rules reflecting the managerial technology. Behind the scenes, sensemaking interprets and adapts to make actual practice (Christiansen and Varnes 2009) giving some flexibility to the rules. So the (partial) mirroring is obtained through established technologies of organizing which can have different levels of independence, hence clustering the sub-organizations for product sub-systems.

Modularity

Modularity and loosed coupling (Sanchez and Mahoney 1996) can then be the purpose of decision-design in order to be able to adapt easily and reached strategic flexibility. Instead of being seen as an adaptation to the environment turbulences, it could also be actively co-designed from the product engineering perspective. Having such approach to modularity could also be envisioned temporarily before reintegration (Siggelkow and Levinthal 2003).

In the BC seat platform project, the aim was to define an architecture and organize modularity. However, such effort was not reached and practices of exploitation took over. The existing interdependencies as well as evolving standards with the modularity choices taken were not made clear to stakeholders to redefine its mirroring.

Platform engineering, or designing a wishful decision by genericity, is an exploration effort as per which exploitation constraints and parameters can be built upon to define new design rules, and consequently organize engineering departments, manufacturing as well as supply chain.

Stress testing: absorbing uncertainty/unknown?

The perspective of modularity and genericity, which is one of the decisions $d^{gen}$ in our model, brings the possibility of managing double unknown situations (Kokshagina et al. 2016) specially through adapted portfolio management. In a similar way, (Hooge et al. 2014), and closer to our concern for decision-design, they showcase the anomaly of willing designing a generic technology to bridge a gap between distant fields and technologies, by opposition to the common evolutionary strategies. Difficulties are raised regarding the sophisticated organizational patterns, and capacity to reuse and connect existing technologies.

Consequently, when considering how the mirroring of interdependencies enacted by members of the organization, the knowledge mobilised in decision-design will require a precise understanding of the levels of independence between elements, boundaries and purpose of each group of other decision-designers involved.

Endogenizing the unknown: dynamically designing projects and organizations

Decisional ambidexterity encourages then to fully endogenize the unknown into project management to address how it can be shaped into organizations through the dynamics of interdependencies mirroring exploitation product engineering.

We then propose to make organization design part of the decision-design model with underlying interdependencies and fixation effects. It will help specifying the nature of decisions covering contingencies that may lie in the intricacies of interdependencies. These should effectively be redesigned depending on the generativity of processes used to propose new alternatives. The latter being one of the issues at stake revealed by the biases induced by organizational ambidexterity and its model of non-mutual conditioning against innovation initiatives.

The model of decisional ambidexterity for mutual conditioning between exploration and exploitation focuses now on decision-designing as well as organization. Consequently, this technology of organizing that simultaneously aims at supporting innovation project management and change management, will spread out and ripple through established processes and structures and hence contributing to the metabolism of an innovative organization.

Organization design in the unknown and against organizational fixation

Organization design requires to be thought differently at the light of decisional ambidexterity, as we force to bring the unknown and its management at the level of projects and interactions around decision-making, now decision-designing. The potential of transformation and attraction, channelled through extended decision spaces, gives a new flavour to the organization design features specially for interdependencies and fixations effects.

The unknown organization design

The difficulty for standard organization design is when considering unknown information of unknown value, as the necessity to establish relationships between agents is hard to justify (Puranam, Raveendran, and Knudsen 2012). And it is not only by having people together that they will be able to solve new problems, let aside formulating new problems themselves. When trying to foresee the future of organization design when facing the unknown, the importance of having a new method for normative field becomes critical (Puranam 2012). The methodology developed over several decades in design theory and reasoning can fortuitously support such initiative.

By considering the importance of action, interaction and decision in organizations, we can centralize such key phenomena into organization design. The contributions of (silent) decision-designers continuously referring to exploitation will help valuing exploration and vice-versa. The multiple interactions required to make sense of decisions, product design and engineering design rules become quite attractive for organizational studies.

For the Design Thinking projects, concepts wouldn’t fit BUs or even multi-BU prospects. Engineering rules had to change, product lines and BUs respective boundaries were contested through the designed and selected concepts by ADT, group VP of Strategy and Business Development, and during multi-BU workshops. The confrontation and adaptation would only rely on a separation of exploration/exploitation regimes. Generative processes were guided by product design objectives, as well as environment perspectives (user value and empathy) but failed to address the potential organization redesign.

Placing the unknown right at the centre of organization design can probably overcome caveats of simple solutions or adjustments that only have a concern for: balance of hierarchical control, individual autonomy and spontaneous cooperation (Keidel 1994). A technology of organizing could then substantiate the generative learning (Senge 1990) by deriving from the decisional ambidexterity model. Such device could help have a better understanding of required organization design and its generative fit (Avital and Te’eni 2009; Van de Ven, Ganco, and Hinings 2013).

Learning can then be overseen in our model as it will have to be challenged as interdependencies will be unlocked, reinforced or reconfigured depending on how the decision-designers explore exploitation and exploit exploration.

Managing interdependencies and organization fixation effects

In the context of meta-organizations (Gulati, Puranam, and Tushman 2012) and also open-innovation, rethinking of organization design can not be seen as fully transposed to problem/task decomposition by leadership (Lakhani, Lifshitz-Assaf, and Tushman 2013). We have seen that the identity of organization can be so strong due to engineering and regulations, that problem formulation in exploration project management can escape from the attraction of organization competence. So, trying to keeping it together, and build new coherence through the transformation triggered by design activities, requires to shift the locus of change down to the micro-level of interdependencies and fixation effects.

In the Icing Conditions detection, the BU manager ended up having a valuable exploration project recognized in the industrial ecosystem but at odds with the organization. Again, we have a case where the exploration was driven by several expansive decisions changing the game but the interdependencies with systems engineering mastered with the business have to be reworked. The transferred unfinished but flight tested product should be seen as a learning device rather than fit for development.

Fixation effects could be associated to the state-of-art in product development, and the gradual convergence towards a common consensus, which may be biased.

Sustaining metabolisms: regenerating the organization

As discussed in the anomalies specification (chapter [chap:anomalies_spec]), embedding change management within project management calls for phenomena rippling across structures and processes, as we propose to do with centrality of action, decision and design for organizing. The biological metaphor of metabolisms allows targeting “processes” that are tied by the double bind of structure and processes. It puts the emphasis on the actionable knowledge and relationships (Segrestin et al. 2017), instead of separating management of structure and process. The constructs of regenerative capabilities and recombination of routines in organization can be then further substantiated with decisional ambidexterity and organizational metabolism.

Regenerative dynamic capabilities

The difficulty associated with the innovation function distributed across projects (Gemünden, Lehner, and Kock 2018) goes to the distributed nature of capabilities. Making the sum won’t be representative of the overall capabilities available in underlying host functional departments. However, by considering they will be organizing their trajectory around decision-design with supplying departments, other business units, as well as external players, can create a pivotal force for stakeholders to understand in which direction change should occur.

For the BC seat platform project, in the early stages of defining the extent and features of genericity, several stakeholders took part in designing concepts, even marginally, but also to designing what had to be decided. The sense made out of those meetings, and its contribution to generating alternatives, represents a capability to regenerate seat engineering. Unfortunately, a similar effort was not sustained when switching from exploration to exploitation due to a strong divide enforced by ambidexterity.

As teams and organization will cope with these different temporalities, first locally at the project level, and then at the program level (Simon and Tellier 2016), it gives us confidence on the value of our model. Temporary-organizing will reach a meta-equilibrium during when designing-decisions, as they make sense and rethink the new coordination mechanisms supporting the new product development. We contribute then to the idea of having regenerative capabilities (Ambrosini, Bowman, and Collier 2009, S15) supported by decisional ambidexterity.

Recombining routines

In a similar way, the idea of recombining routines (Cohendet and Simon 2016) fostered by a single project, can be the occasion to rethink product design rules that have been fixated for some time. In their case, they specify the importance of meetings held, prototypes and proof of concepts that were tailored and managed by project manager to make a case for a radical product concept, at odds with exploitation regime. Resurfacing interdependencies and design fixation with such practices can be a means to make tacit the designing of decisions and learning mechanisms that can be mapped with C-K theory as we did in the previous chapter.

What is also stimulating here is that, innovation management does necessarily have to supported by additional routines. Within a set of routines, they can be reconfigured to create more value, as if the scales and units changed in nature. It is what we tried to picture with the Pareto front and reaching out for alternatives (see section).

In Design Thinking cases, some concepts actually implied recombining routines across business units who were traditionally segregated by the market and engineering standards. Focusing on the product and design rules would only force adaptation, whereas the obstacle was rather on elevating interactions on the how and its legitimacy for users, but also the remaining effort: change in sales pitch, market channel, one-time qualification, evolving standards and certification forms, etc.

Finally, it would be such contextuality that could be associated with contextual ambidexterity but detailed in its interaction modes (Birkinshaw and Gupta 2013). It would now make more sense with the limitations on the nature and dichotomy of exploration/exploitation regimes discussed in the very same paper and in (Gupta, Smith, and Shalley 2006).

The networking effect (Christiansen and Varnes 2007) can easily be structured around the dialogue interdependent and fixation knots. It encourages channelling the access to (distant) knowledge, legitimize the mutual conditioning between exploration and exploitation (Simon and Tellier 2011). But here again, we insist on the technology of organizing collective action through decisional ambidexterity facilitating the grounding of such interactive patterns.

Full model synthesis

We have then specified the interest of having organization design embedded in the designing of decisions, by considering that organizations are part of the knowledge required to enact decision concepts. Consequently, we propose simply to represent in the C-K formalism what makes decision and its hypotheses with organizational ties and mirroring: interdependencies and fixation effects. They are the translation at the organizational level that can be easily disturbed by generative processes: i.e. where tension and anomalies come from between models of ambidexterity and exploration project management. In other words, we insist once again on the link between actionable knowledge and relationships, and how it can metabolize innovation in the organization with its structure and processes.

Listing the engineering design fixations, interdependencies and built-in product architecture, will help addressing the regenerative dynamic capabilities and recombination of routines required to manage the organizational metabolism. The change management will then be steered through the inter-relationships bearing generative learning triggered by the collective decision-designing. It is again the mutual conditioning of exploration and exploitation which allows simply measuring change. In the following table [table:modelADMtabfull], we can complete the model synthesis with the descriptors derived from previous literature review. We remember the synthetic literature model of non-mutual conditioning enabling its comparison with decisional-ambidexterity model which blends the conditioning between exploration and exploitation. It allows overcoming biases induced by organization ambidexterity and its limitations such as neglect of organization design fixations revealed by exploration project management.

| Model descriptors | Non-mutual conditioning | Mutual conditioning extended model |

|---|---|---|

| Model of coordination and collective action | 1. Not necessarily on the same continuum, exploration and exploitation call for two dissociate action regimes. 2.Balancing is left as a paradox at different levels of analysis: structure (centralization, distribution), time and individuals. |

1. Exploration and exploitation are mutually used to support extended decision-making. 2. The balancing paradox is dealt by design operators valuing mutual benefits of exploration and exploitation. Decision-designers interactively unlock and manage (new) interdependencies and (organizational) design fixations. A form of governance may be required to orchestrate and sustain such practice. |

| Generative processes | 3. The nature of generative processes supporting exploration appears quite free, random and sometimes even foolishness-based. 4. Generativity of the product development may not be sustained by (temporary) organizations (floating issue). 5. The performance and reference is light structured: reduced to a selection issue or sometimes to complex interactionist phenomenon. |

3. Generative processes target the exploration/exploitation bone of contention and associated decision-making. 4. Generativity is articulated around design fixations and interdependencies for better interactive value management with other (silent) decision-designer. 5. Performance is repositioned on the transformative feature of decision-design where its criteria are redefined. Managing the organizational mirroring of interdependencies and fixations is part of the performance assessment. |

| Environment cognition | 6. One-way interaction: Environment to Organization. 7. The environment structures the response, nature and distribution of generative processes. 8. The environment is used to augment the product development requirements. |

6. The environment is managed through the design of decision to realize designed states of nature. 7. The decision-design addresses environment-induced fixations. 8. The environment awareness developed through decision-design targets also (potential) interdependencies, future exploitation features, and organization design fixations induced by environment. |

| Organization design | 9. Organization design is pre-conceived or uncontrolled. 10. Organization design creates gaps for managing generative processes and the dynamics of their organizational ties. |

9. Organization design is simultaneously managed with decision-design in project management as it has explored exploitation interdependencies and fixations. 10. Relationships and actionable knowledge are concurrently managed through decisional-ambidexterity thus embedding the organizational change management. |

Chapter synthesis: decisional ambidexterity and organization design

This chapter has extended the first version of decisional ambidexterity model with our concern for organization design and change management. We are then able to satisfy the requirements defined in chapter 7.

We re-use the idea of simultaneity of change management with project management (Pollack 2017) to endogenize the unknown further with decision-design perspective. Organization design and regenerating capabilities were included as knowledge elements required to generate new decision concepts and enabling the organization of collective action supporting them. We can then manage a metabolism sustaining innovation effort through organizational change. Our model should be considered as basis for technology of organizing to orchestrate and channel interactions for decision-designers contribution to exploration project management and dynamically mirrored organizational change.

The anomalies were discussed at the light of decisional ambidexterity. The case studies reveal several features of decisional ambidexterity and why they were misunderstood given models of ambidexterity.

Consequently, we have a full model of mutual conditioning between exploration and exploitation capable of explaining the descriptors reconciling with the identified literature models’ limitations: model of coordination and collective action, and the innovation potential of attraction (generative processes, environment cognition, organization design).

References

Adler, Paul S. 1995. “Interdepartmental Interdependence and Coordination: The Case of the Design/Manufacturing Interface.” Organization Science 6 (2): 147–67. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.6.2.147.

Ambrosini, Véronique, Cliff Bowman, and Nardine Collier. 2009. “Dynamic Capabilities: An Exploration of How Firms Renew their Resource Base.” British Journal of Management 20 (SUPP. 1): S9–S24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2008.00610.x.

Avital, Michel, and Dov Te’eni. 2009. “From generative fit to generative capacity: exploring an emerging dimension of information systems design and task performance.” Information Systems Journal 19 (4): 345–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2575.2007.00291.x.

Birkinshaw, Julian, and Kamini Gupta. 2013. “Clarifying the distinctive contribution of ambidexterity to the field of organization studies.” The Academy of Management Perspectives 27 (4): 287–98.

Campbell, Donald T. 1979. “Assessing the impact of planned social change.” Evaluation and Program Planning 2 (1): 67–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/0149-7189(79)90048-X.

Christiansen, John K., and Claus J. Varnes. 2007. “Making decisions on innovation: Meetings or networks?” Creativity and Innovation Management 16 (3): 282–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8691.2007.00441.x.

———. 2009. “Formal rules in product development: Sensemaking of structured approaches.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 26 (5): 502–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5885.2009.00677.x.

Cohendet, Patrick, and Laurent Simon. 2016. “Always Playable: Recombining Routines for Creative Efficiency at Ubisoft Montreal’s Video Game Studio.” Organization Science 27 (3): 614–32. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2016.1062.

Colfer, Lyra J., and Carliss Y. Baldwin. 2016. “The mirroring hypothesis: Theory, evidence, and exceptions.” Industrial and Corporate Change 25 (5): 709–38. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtw027.

Davies, Andrew, Stephan Manning, and Jonas Söderlund. 2018. “When neighboring disciplines fail to learn from each other: The case of innovation and project management research.” Research Policy 47 (5): 965–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.03.002.

Gemünden, Hans Georg, Patrick Lehner, and Alexander Kock. 2018. “The project-oriented organization and its contribution to innovation.” International Journal of Project Management 36 (1): 147–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2017.07.009.

Gulati, Ranjay, Phanish Puranam, and Michael Tushman. 2012. “Meta-organization design: Rethinking design in interorganizational and community contexts.” Strategic Management Journal 33 (6): 571–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.1975.

Gupta, Anil K, Ken G Smith, and Christina E Shalley. 2006. “The Interplay Between Exploration and Exploitation.” Academy of Management Journal 49 (4): 693–706. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2006.22083026.

Hatchuel, Armand, Benoît Weil, and Pascal Le Masson. 2006. “Building innovation capabilities. The development of design-oriented organizations.” In Innovation, Learning and Macro Institutional Change: Patterns of Knowledge Changes, edited by J T Hage, 1–26. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Hooge, Sophie, Olga Kokshagina, Pascal Le Masson, Kevin Levillain, Benoit Weil, Vincent Fabreguettes, and Nathalie Popiolek. 2014. “Designing generic technologies in Energy Research: learning from two CEA technologies for double unknown management.” In European Academy of Management - Euram 2014, 33. Valencia, Spain. https://hal-mines-paristech.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00987214.

Hornstein, Henry A. 2015. “The integration of project management and organizational change management is now a necessity.” International Journal of Project Management 33 (2): 291–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2014.08.005.

Keidel, R. W. 1994. “Rethinking organizational design.” Academy of Management Perspectives 8 (4): 12–28. https://doi.org/10.5465/AME.1994.9412071698.

Kokshagina, Olga, Pascal Le Masson, Benoit Weil, and Patrick Cogez. 2016. “Portfolio Management in Double Unknown Situations: Technological Platforms and the Role of Cross-Application Managers.” Creativity and Innovation Management 25 (2): 270–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12121.

Lakhani, Karim R., Hila Lifshitz-Assaf, and Michael Tushman. 2013. “Open Innovation and Organizational Boundaries: The Impact of Task Decomposition and Knowledge Distribution on the Locus of Innovation.” In Handbook of Economic Organization, edited by Anna Grandori, 355–82. 1. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Lenfle, Sylvain. 2016. “Floating in Space? On the Strangeness of Exploratory Projects.” Project Management Journal 47 (2): 15. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmj.21584.

O’Connor, Gina Colarelli. 2016. “Institutionalizing corporate entrepreneurship as the firm’s innovation function: reflections from a longitudinal research program.” In Handbook of Research on Corporate Entrepreneurship, edited by Shaker Zahra, Donald Neubaum, and James Hayton, 145–74. Northampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Pollack, Julien. 2017. “Change Management as an Organizational and Project Capability.” In Cambridge Handbook of Organizational Project Management, edited by Shankar Sankaran, Ralf Muller, and Nathalie Drouin, 236–49. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316662243.021.

Puranam, Phanish. 2012. “A Future for the Science of Organization Design.” Journal of Organization Design 1 (1): 18. https://doi.org/10.7146/jod.6337.

Puranam, Phanish, Marlo Raveendran, and Thorbjørn Knudsen. 2012. “Organization Design: The Epistemic Interdependence Perspective.” Academy of Management Review 37 (3): 419–40. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2010.0535.

Sanchez, Ron, and Joseph T. Mahoney. 1996. “Modularity, Flexibility, and Knowledge Management in Product and Organization Design.” Strategic Management Journal 17: 63–76. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004.

Segrestin, Blanche, Franck Aggeri, Albert David, and Pascal Le Masson. 2017. “Armand Hatchuel and the Refoundation of Management Research: Design Theory and the Epistemology of Collective Action.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Organizational Change Thinkers, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-49820-1.

Senge, Peter. 1990. “Leaders’ new role: building learning organizations.” MIT Sloan Management Review.

Siggelkow, Nicolaj, and Daniel A. Levinthal. 2003. “Temporarily Divide to Conquer: Centralized, Decentralized, and Reintegrated Organizational Approaches to Exploration and Adaptation.” Organization Science 14 (6): 650–69. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.14.6.650.24840.

Simon, Fanny, and Albéric Tellier. 2011. “How do actors shape social networks during the process of new product development?” European Management Journal 29 (5): 414–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2011.05.001.

———. 2016. “Balancing contradictory temporality during the unfold of innovation streams.” International Journal of Project Management 34 (6): 983–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2016.05.004.

———. 2018. “The ambivalent influence of a business developer’s social ties in a multinational company.” International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management 22 (1-2): 166–87. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEIM.2018.089718.

Stan, Mihaela, and Phanish Puranam. 2017. “Organizational adaptation to interdependence shifts: The role of integrator structures.” Strategic Management Journal 38 (5): 1041–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2546.

Stjerne, Iben Sandal, and Silviya Svejenova. 2016. “Connecting Temporary and Permanent Organizing: Tensions and Boundary Work in Sequential Film Projects.” Organization Studies 37 (12): 1771–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840616655492.

Van de Ven, Andrew H., Martin Ganco, and C. R. (BOB) Hinings. 2013. “Returning to the Frontier of Contingency Theory of Organizational and Institutional Designs.” The Academy of Management Annals 7 (1): 393–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520.2013.774981.